Wherever you go, there’s bound to be someone talking about how they wish they were “more productive”. Maybe that’s you. Productivity has become the central focus on everyone’s minds, especially in America. Efficiency is the new virtue, which is why productivity enhancement has become a multibillion-dollar industry and is flooding social media sites. We have a strong desire to optimize our lives and carve out a better future for ourselves, but most of us miss the core tenants to real productivity.

128 years before Atomic Habits was released to the public and sold over 20 million copies, there was another “James” who published a masterpiece on the power of habits that towers over James Clear’s advice.

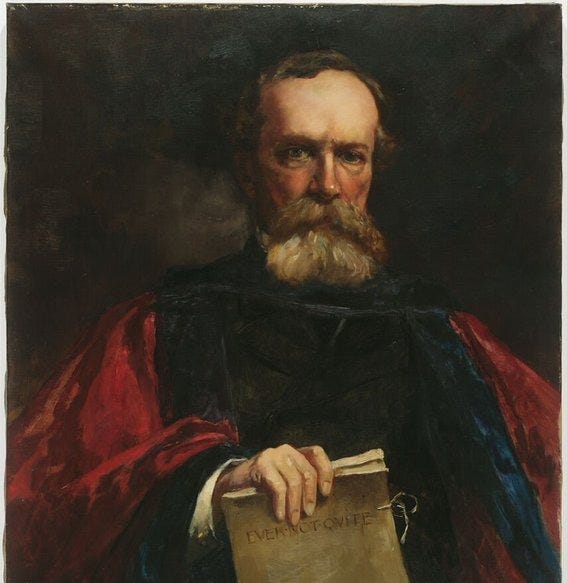

The godson of Ralph Waldo Emerson, professor to Theodore Roosevelt, founder of the oldest American psychological society, and Amazonian explorer William James garners little more than a few paragraphs in most psychology textbooks today. Once regarded as a titan of psychology, his aura has faded from the modern psychology and his work now gathers dust.

William James, fathered the American Psychological movement, and established the philosophical school of “Pragmatism”—a revolution in both psychology and philosophy. In 1890, he published a seminal book, Principles of Psychology, that shaped the direction of the modern psychology we know today.

In that work, he dedicated a chapter to developing proper habits, a chapter that changed how I see even the most dreaded of tasks.

Here’s 8 of the finest lines he penned in his chapter on habits:

1. Don’t Feel: Do.

"There is no more contemptible type of human character than that of the nerveless sentimentalist and dreamer, who spends his life in a weltering sea of sensibility and emotion, but who never does a manly concrete deed.”

To understand William James’ psychology—the way mental life is ordered—it’s important to understand his wider philosophy. James was enamored by the ideas of one man in particular: John Stewart Mill, the famous proponent of Utilitarianism. He even goes as far as to dedicate his book Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking to Mill. What James accomplishes in this work is bringing the much-needed counter to the airy and romantic theory coming from Enlightenment thinkers, which permeates throughout his approach to psychology.

James rightly identified that there is no room for sentimentalism and dreams on the shelf of excellence.

To achieve anything, you must act.

Our well-being is predicated on activity. For example; we need to act in order to create new neuronal connections, which then allows us to improve, grow, and function. Without action we stagnate, so whatever stops us from doing must be overcome.

Feelings are natural, so of course it’s okay to have them. We consider feelings to be part of the human experience; joy, sorrow, terror, ecstasy, anger, etc. But it’s important to understand the role of emotions and their place in the hierarchy of Being.

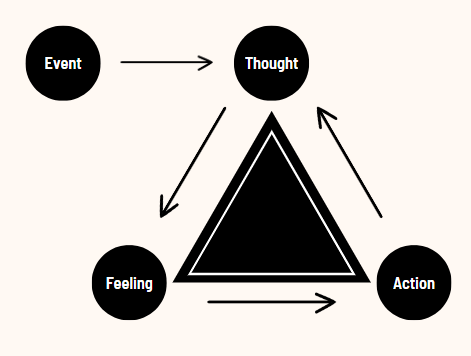

The prevalent theory in psychotherapy today is Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Developed by Aaron Beck in the 1960s, it highlights the role our thoughts (cognitions) have on our feelings and subsequent actions.

As you can see, this loop is triggered by anything we can label as an event, which triggers an interpretation (thought), which then communicates the amount and type of fuel (emotion) we need to eventually respond (action). Any action we carry out then influences our next interpretation as it relates to the event.

If someone’s stuck in the emotion stage of this loop, and does not act, they simply don’t receive feedback that would be necessary to alter future thoughts, feelings, and actions. The “sentimentalist” then becomes someone who is repeatedly acted on by external events and never exercises his or her will, most often resulting in a frail and victimized existence.

The only response we muster up is pity for this pusillanimous individual as we recognize they are the source of their own despair. You can’t take pity to the bank. Feelings are as ephemeral as the morning fog, so there’s no use in trying to hold on.

James rightly expresses the fundamental building block for success as action, which is essential to understanding the rest of his guidelines for proper habits.

2. Build Your Savings.

The great thing, then, in all education, is to make our nervous system our ally instead of our enemy. It is to fund and capitalize our acquisitions, and live at ease upon the interest of the fund. For this we must make automatic and habitual, as early as possible, as many useful actions as we can, and guard against the growing into ways that are likely to be disadvantageous to us, as we should guard against the plague.

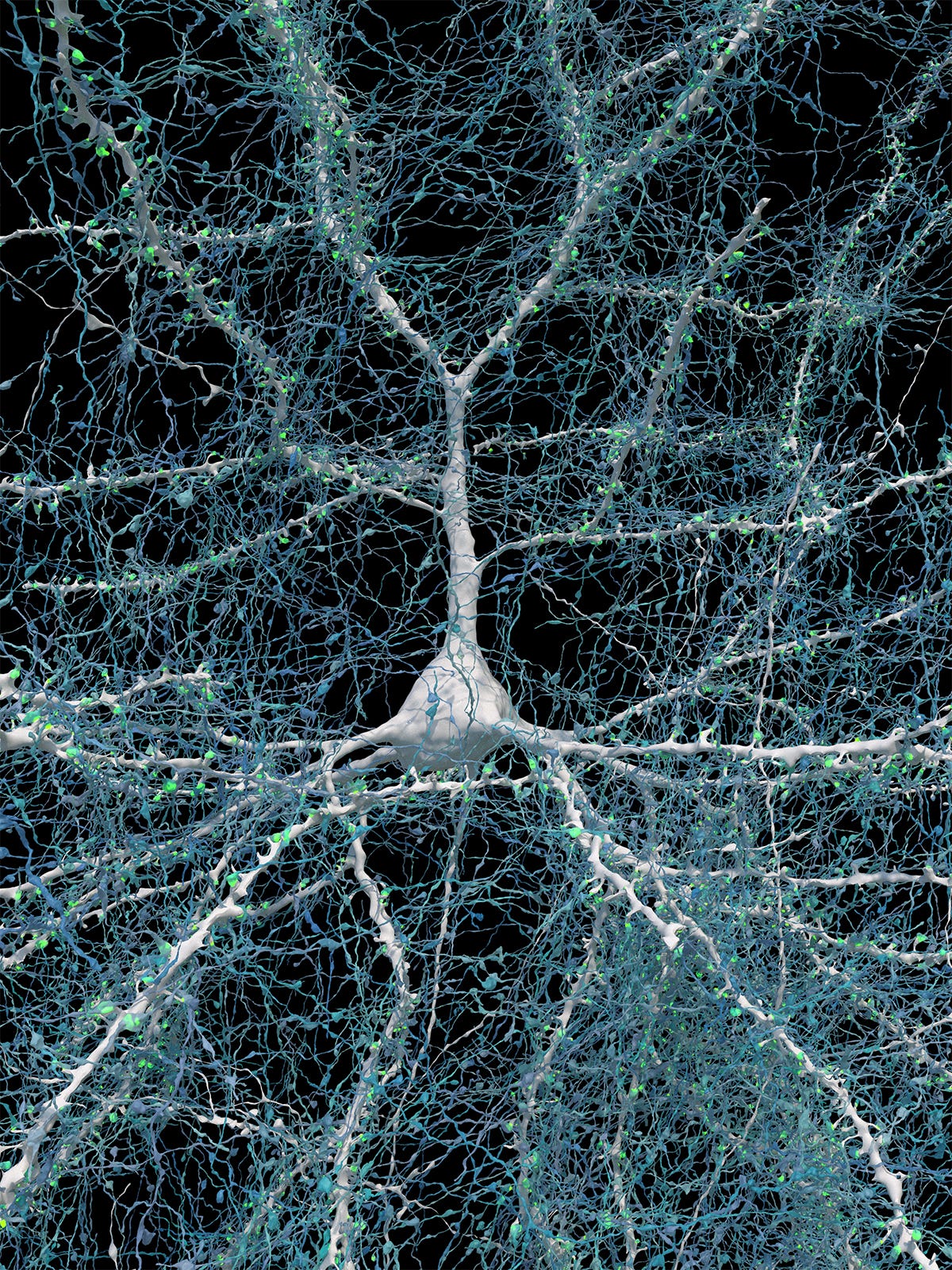

To understand why James’ advice is so crucial, we need to take a peak into our understanding of neuroscience today and how this idea was purely visionary. I won’t pretend to understand all of the neuroscience, so I’ll try to keep it simple.

Your brain contains roughly 100 billion nerve cells called neurons. These are responsible for storage of information, direction of movement, thoughts, and every other function of a human being. Everything you’re able to do is because of your brain—it’s the chief organ and directs the orchestra that is your body.

Researchers carried out a study this past year to work on creating a high-resolution picture of its structure. They cut away a 1-millimeter section of human brain tissue (the thickness of most credit cards) to try and accomplish this, and here’s what they found:

“Presented here is a computationally intensive reconstruction of the ultrastructure of a cubic millimeter of human temporal cortex that was surgically removed to gain access to an underlying epileptic focus. It contains about 57,000 cells, about 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and about 150 million synapses and comprises 1.4 petabytes [1,400,000 gigabytes].”

Most laptops today operate very well on 500 gigabytes. The first moon landing was done with far less than that.

Your mind has a seriously astounding capacity. Honestly, I’m astounded as I type this…

Every action has a consequence, which then informs future action.

Your brain makes connections based on those actions. Those connections become easier to evoke the more they’re practiced. These become patterns of behavior after a period of time.

How we act today influences how we’ll act tomorrow. Not only that, but it compounds and becomes more prominent, like an investment, as James states.

Every positive helps us grow toward a good life, virtuous life, while every poor behavior lends itself to our destruction.

How does education fit in here?

Education teaches us what to value; thus education teaches how to act because we always act toward our values.

Making our nervous system our ally is then, as James states, the great task of education.

3. The Best Time to Start is Now

“There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation. Full half the time of such a man goes to the deciding, or regretting, of matters which ought to be so ingrained in him as practically not to exist for his consciousness at all. If there be such daily duties not yet ingrained in any one of my readers, let him begin this very hour to set the matter right.”

This is a doubling down of the first quote. It’s also an expansion of it.

The first focused on the feelings which might prevent someone from acting, this highlights the consequences.

What James is saying here is basically this:

“WHAT A WASTE OF TIME IT IS TO NOT HAVE PROPER HABITS!”

Imagine a world where you deliberate every action other than breathing, and maybe even that from time to time to boot. Maybe that’s you right now. Perhaps it was you in the past. But let’s sit in that for a moment.

.

..

…

You should have noticed how even with that space, you had some compulsion to act.

Why?

Because the number of things to do floods in and it’s overwhelming. To have no set pattern for your day is to invite chaos, anxiety, and stagnation.

“I’m a free spirit” or “I go with the flow” may be a response to this.

They’re responses that I can vouch for, since I can recall my adolescent self-uttering these very words as a defense against the responsibility and disciple being instructed.

I’ll simply state that, while that can be something we tell ourselves, reality does not care and will dole out our fortunes accordingly.

Thankfully, I heeded James’ warning (unknowingly at first) and have benefited materially, mentally, and spiritually.

The best time to start was 3 years ago. The second best time to start is right now.

4. The Origin of the Hero

That is, be systematically ascetic or heroic in little unnecessary points, do every day or two something for no other reason than that you would rather not do it, so that when the hour of dire need draws nigh, it may find you not unnerved and untrained to stand the test. Asceticism of this sort is like the insurance which a man pays on his house and goods. The tax does him no good at the time, and possibly may never bring him a return. But if the fire does come, his having paid it will be his salvation from ruin. So with the man who has daily inured himself to habits of concentrated attention, energetic volition, and self-denial in unnecessary things. He will stand like a tower when everything rocks around him, and when his softer fellow-mortals are winnowed like chaff in the blast

The purpose of education is not only to train your sword arm to hack through the myriad obstacles standing in your way, although that is a significant portion of its purpose, it’s also to defend and preserve yourself when you’re on the back foot.

This is the final suggestion he gives to becoming a champion of yourself—do things solely because they’re hard, so you might not be pummeled by misfortune when it comes.

Notice how he says it doesn’t have to be every day, but frequent enough that you stay practiced in the art of overcoming. We mustn’t fall into some masochist nonsense that strays us from our task. That’s obviously counterproductive. But so is doing nothing at all.

We should also not read this as “only do physically strenuous activities”, that would be misunderstanding the assignment. James states that we should do something “for no other reason than that you would rather not do it…” While working out can be strenuous, it might take a little bit of motivation to get your rear to the gym, and it may have been a while since you hit the weights, digging a little deeper will reveal what we should set ourselves toward.

What James means in this section has to do with the human faculty of will. I briefly mentioned it earlier, so I hope this helps make sense of it if you’re unfamiliar.

The will is the part of the person that initiates action. It’s what turns potential energy into kinetic energy—the human will is that active force within which sets us out on our task. It jolts you up from your seat and demands that you act, even if you’ve yet to discover what for. It’s perhaps the most essential faculty to human existence, and James understands that, as he spent another chapter of the Principles of Psychology exploring the will (my favorite chapter).

To exercise the will, we must act in a way we know is difficult for us, yet continue in that task for the sole purpose of its difficulty. That might mean going to the gym, but could also mean putting away the laundry in the corner, cleaning the dishes in the sink, or reading the book you had put on your side table six months ago and swore to read.

Any way we can pay toward bolstering our insurance policy is a step in the right direction. In my article on loneliness, I argue for another reason why becoming masters of ourselves is so vital.

You can read that here:

A Holistic Answer to The Loneliness Epidemic Plaguing Young Americans

“The common suffering is the alienation from oneself, from one’s fellow man, and from nature; the awareness that life runs out of one’s hand like sand, and that one will die without having lived; that one lives in the midst of plenty and yet is joyless.”

No one will take a policy out for you; no one will come to save you when you need it most.

Prepare yourself to stand like a strong tower when the blast comes, because it will come.

5. The Purpose of Knowledge is Action

"No matter how full a reservoir of maxims one may possess, and no matter how good one's sentiments may be, if one have not taken advantage of every concrete opportunity to act, one's character may remain entirely unaffected for the better. With mere good intentions, hell is proverbially paved. And this is an obvious consequence of the principles we have laid down.”

There are few things more prominent online than what I’ve come to term “quote culture”. Simply put, it’s the overinflation of one-liners to the point of believing there’s something significant gained by their consumption.

“Now hold on, this whole article is a collection of quotes, Devan, you’re being hypocritical!”

Take it easy, allow me to explain.

Quotes largely serve as heuristics (mental shortcuts) to get to the proverbial point. They’re excellent for concise communication but they’re an island, and that’s a problem.

Hundreds of accounts on every social media platform are dedicated to spewing quotes to “motivate” and “encourage” others.

There seems to be the belief that those quotes illuminate some kind of knowledge that leads someone to become more enlightened and transform them by virtue of the quote itself.

Even with someone of substance, copying all of the Goodreads snippets possible doesn’t give Ralph Waldo Emerson any real “oomph”. They’re darts thrown carelessly about. When we lack the rest of the context, we’ve kept ourselves from the real value of that idea.

That’s not to say quotes can’t spark someone to venture in a positive direction or inspire them to do something of value, but that quote is then something that’s contextualized, which carries the meaning. There has to already be an aim.

Hopefully, that’s what I’ve done here: provided more context to the quest you’ve already set out on. How? By reading this post, you’ve surmised that you have a need to reach for more.

But if that’s not enough, again, share this post and you’ll get a digital copy of James’ book directly in your inbox.

There’s nothing actionable about a quote—it’s completely empty from a pragmatic perspective. How can the proof be in the pudding if you never made the damn pudding?

You will continue to wonder why your daily mantra has no effect on the actual outcomes you desire until you have “taken every concrete opportunity to act.”

6. Society Falls When You Fail.

Habit is thus the enormous fly-wheel of society, its most precious conservative agent. It alone is what keeps us all within the bounds of ordinance, and saves the children of fortune from the envious uprisings of the poor. It alone prevents the hardest and most repulsive walks of life from being deserted by those brought up to tread therein… It dooms us all to fight out the battle of life upon the lines of our nurture or our early choice, and to make the best of a pursuit that disagrees, because there is no other for which we are fitted, and it is too late to begin again… Already at the age of twenty-five you see the professional mannerism settling down on the young commercial traveler, on the young doctor, on the young minister, on the young counsellor-at-law. You see the little lines of cleavage running through the character, the tricks of thought, the prejudices, the ways of the 'shop,' in a word, from which the man can by-and-by no more escape than his coat-sleeve can suddenly fall into a new set of folds. On the whole, it is best he should not escape. It is well for the world that in most of us, by the age of thirty, the character has set like plaster, and will never soften again.

When we think larger than the immediate personal effects of habits, we quickly run into how they impact society.

Habits that are stretched out and common to all within a community of sorts, they become a part of the culture of that community. As time crawls on, as it likes to do, those habits become a tradition.

James states that by twenty-five, the habits one chooses begin to set in and that it’s best for us to accept our position and operate the best we can within our scope. If this is how society is to operate, then the recipe for a disordered society becomes clearer: a wealth of indecisive people who’ve been told, “You can be anything you want to be”. No direction, no aim, no movement. Societies die with that kind of ambiguity.

A “conservative agent” is an active force, not a static one—it’s a verb.

Habit is that conserving agent for a society, and a society whose fundamental habits have been dismantled, replaced, inverted, and otherwise neglected tends to not do so well. That is the fundamental lie of progress.

We’re taught that progress, in and of itself, is a good thing; it’s all we can hope to accomplish. The simple yet major issue with believing that any movement from the previous order is “progress” is simple: cancer is considered a perfectly reasonable member of society on those grounds.

Setting up a society is a tedious task and is what helps us move toward a more agreeable present and flourishing future. Let’s make sure we set our lives up according to the final words of this quote, such that we’re okay if our character were to “set and harden like plaster” at this very moment.

If that frightens you, start to make the change immediately.

7. Competence > Education

Let no youth have any anxiety about the upshot of his education, whatever the line of it may be. If he keep faithfully busy each hour of the working day, he may safely leave the final result to itself. He can with perfect certainty count on waking up some fine morning, to find himself one of the competent ones of his generation, in whatever pursuit he may have singled out. Silently, between all the details of his business, the power of judging in all that class of matter will have built itself up within him as a possession that will never pass away. Young people should know this truth in advance. The ignorance of it has probably engendered more discouragement and faint-heartedness in youths embarking on arduous careers than all other causes put together.

There’s no question that massive gaps in our education exist. A Gallup poll shows that over 1/4 of Americans are “completely dissatisfied” with the state of American education.

I become upset, at times, when a gap in my own education surfaces because I wasn’t “taught this” or “read that” during my primary schooling years. It’s frustrating to feel that you weren’t given what you believe you deserve. Resentment becomes the default very quickly when discussing education when these thoughts and feelings are floating in the background.

What I’ve come to learn, in part from this passage in particular, is twofold.

I can choose to continue learning in whatever direction I now decide; as James states, “keep faithfully busy each hour of the working day” to succeed long term. It’s up to me.

Any education that isn’t self-directed will fall short of your expectations in some way.

The very nature of a systematized education means personalization will always lack, even for homeschooling (although there’s obvious advantages to that model). We can complain, spit, and holler all we want… or we can do something about it. We’ll talk more about how to exactly personalize your education, but this is the solution—give yourself the education you want.

We get caught up with credentialism—the belief that you need a specialized degree or certification in order to be properly qualified to discuss or even read about a certain topic—but that’s a fool’s notion.

I worked as a graduate assistant for two years while working on my master’s degree and had the opportunity to be a member of a couple faculty committees as a student representative. This allowed me to see behind the curtain and having “Ph.D.” behind your name was zero indication of upper-level reasoning.

While it’s nice to have a piece of paper stating you’ve met the requirements to display that you’ve “really learned” something, it’s doesn’t guarantee that you’ve learned anything! The general thought is that by earning a degree, you’ll become competent and capable to a certain level. However, with the advent of the internet, let alone AI chatbots, and the easing of educational rigor itself, it’s harder now than ever to say with confidence that someone is truly knowledgeable and capable of the level of work we seek from an educated person.

In light of these facts, especially the skepticism we should keep toward credentialism, it’s best to direct your own learning, should you feel it’s not up to snuff.

You will one day find yourself among the competent ones of your generation, in whatever field you set out upon.

8. No Exceptions!

Never suffer an exception to occur till the new habit is securely rooted in your life. Each lapse is like the letting fall of a ball of string which one is carefully winding up; a single slip undoes more than a great many turns will wind again. Continuity of training is the great means of making the nervous system act infallibly right … It is surprising how soon a desire will die of inanition if it be never fed.

This is the most important lesson James gives on building proper habits. It’s also the hardest one to follow.

Key to fulfilling every lesson prior, not allowing exceptions to the rules you’re trying to set is where I see most people fail. Giving way to circumstance is how habits fail. All of that talk on developing your will goes out the window should you fail in letting your habit slip for just a moment.

During a tough practice, my former football coach once barked, “There’s the easy way and then there’s the right way.” While we could get philosophical about “what’s really right”, I’ve come to appreciate this lesson for what it is.

When difficulties appear, we can either shy away from the struggle or embrace it.

Sure, the habits we set can be, and often are, inconveniences in our daily routines and the comfort we’ve built up over the years, but the end we’ve identified when we first set out should have been firm and thought out enough for us to have the courage to make the sacrifice necessary. In other words, we should have a clear plan and reason for our goals and avoid frivolously launching ourselves toward a new end.

James did not miss this of course, as he lists this as the very first step to cementing good habits:

In Professor [Alexander] Bain's chapter on "Moral Habits" [from The Emotions and the Will, 1875]...two great maxims emerge from his treatment. The first is that in the acquisition of a new habit, or the leaving off of an old one, we must take care to launch ourselves with as strong and decided an initiative as possible. Accumulate all the possible circumstances which shall re-enforce the right motives; put yourself assiduously in conditions that encourage the new way; make engagements incompatible with the old; take a public pledge, if the case allows; in short, envelop your resolutions with every aid you know...

To avoid letting your habits slip, you must provide yourself with the strongest reasons for carrying out each habit, then alter your environment to encourage every possible execution of that habit within reason. When you stay consistent, you’re allowing those neurons to connect again, and again, and again, leaving yourself no choice other than to do your duty.

Recap

This ended up being a tad longer than I initially expected, so let’s recap just a moment.

Without the discoveries of William James, modern psychology may look very different. Not only that, James captures the zeitgeist of the American mind in a philosophy called Pragmatism, based on the ideas of John Stewart Mill.

In his masterpiece, Principals of Psychology, he dedicates a chapter to Habits. There are 9 lessons that I believe are vital to developing proper habits, and they are as follows:

To achieve anything, you must act.

Making your nervous system our ally instead of your enemy.

It’s a waste of time to not have good habits! Get after it!

Prepare yourself to stand like a strong tower when the blast comes, because it will come.

Words are only words—you must take action for them to matter.

You hold up society, don’t let it fall.

Your formal education is not a predictor for your future success, you are. Command your learning.

Embrace the difficulty of consistency.

Launch yourself, first and foremost, as strongly and decidedly as possible.

Billions of dollars are spent on productivity each year, but nearly every tool and product aims at one or more of these truths. James was able to capture something truly evergreen about human habits and our broader psychology.

In sum, act decidedly, don’t slip up, and find your will by being heroic everyday.

Thanks for reading and dont’ forget to let me know what you thought!

See you next time!

Devan