“The common suffering is the alienation from oneself, from one’s fellow man, and from nature; the awareness that life runs out of one’s hand like sand, and that one will die without having lived; that one lives in the midst of plenty and yet is joyless.”

~Erich Fromm

Erich Fromm, drawing from his experience as a psychoanalyst, echoes an all too human experience:

Alienation. Isolation. Loneliness. Hopelessness.

Common to humans throughout history, these feelings of alienation naturally lead to suffering.

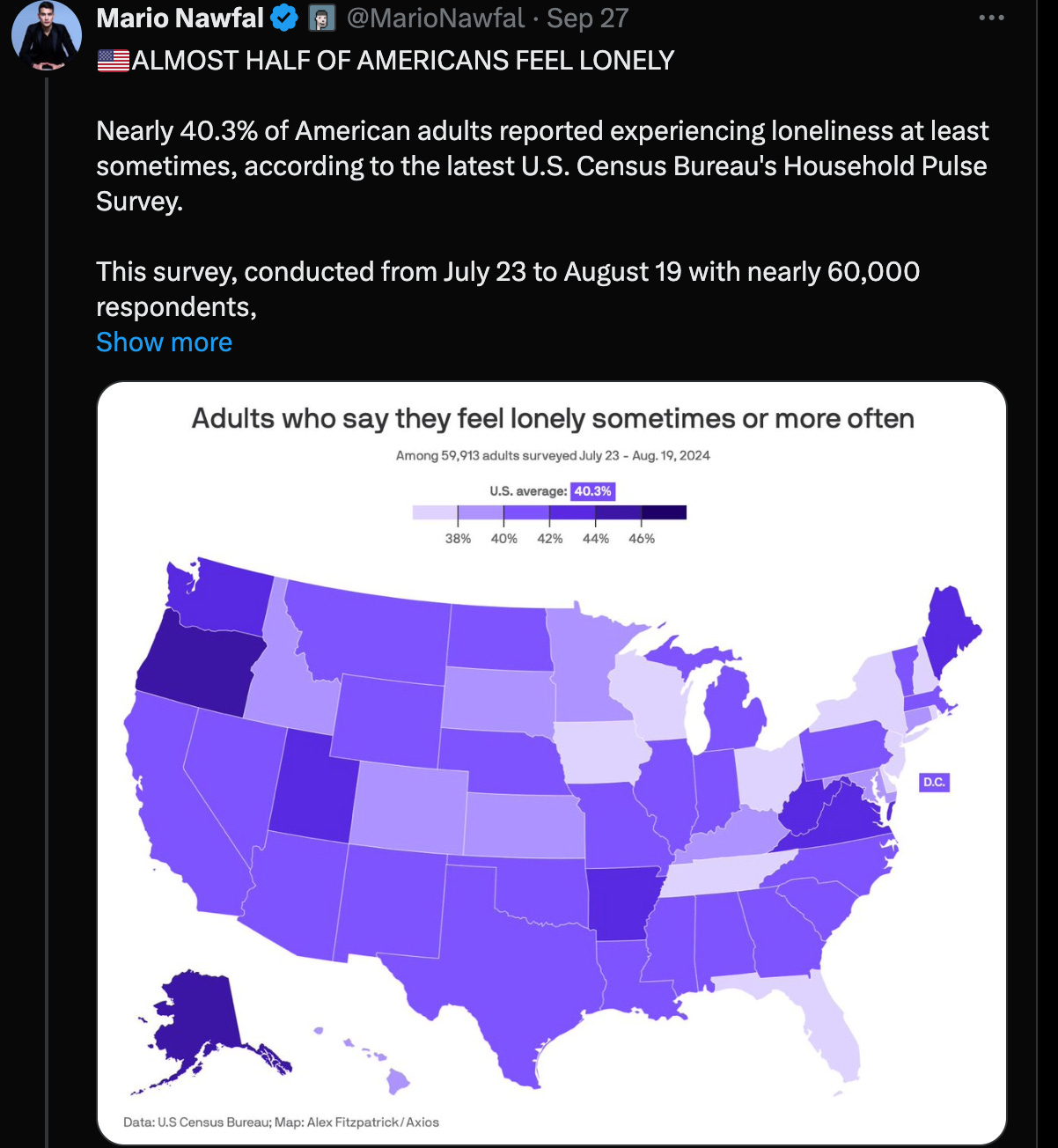

Countless headlines in the last decade have brought attention to the fact that we, the Western developed world, are suffering from a loneliness epidemic.

Over 1/3 of adults in the US report feeling lonely at least some of the time. That’s nearly 100 million people reporting that they feel lonely in the last year.

Other countries aren't far behind:

"Nearly one in four people worldwide -- which translates into more than a billion people -- feel very or fairly lonely, according to a recent Meta-Gallup survey of more than 140 countries."

Loneliness is not only an undesirable feeling, it has deadly consequences.

A recent study that examined over 5000 adult suicide cases found that the strongest and most prevalent risk factor for someone completing suicide was social isolation.

In crisis training, I learned that there are two things to look for in a client who may be suicidal: (1) do they believe they’re a burden to others, and (2) have they failed to integrate into a social group.

Both are symptoms of extreme loneliness.

We’re considered the most connected generation, thanks to the power of mass communication and the internet, yet simultaneously the most alone.

You’d think that with the power to connect anytime, anywhere, we’d have stronger and deeper connections to others and be able to foster and grow new and old friendships alike.

I won't dismiss the fact that because of the internet, people with similar interests have connected across the globe and made impactful bonds.

Unfortunately, the problem is much deeper than merely not having friends or social connection, it’s a result of the mistreatment of our psychological development itself.

Loneliness is an internal state of mind that is independent of external influences—it doesn’t matter if you have great friends, a spouse, children, are involved in your community, or even good coworkers, loneliness is beyond that.

Many who report feeling lonely also report guilt about their feelings:

“I feel so selfish because everyone else is happy to be around me, except for me.”

or

"No matter what I do, where I go, I always feel alone."

Loneliness alters the flow of information from the external world and clouds our thinking.

Nothing feels exactly "right" when the plague of loneliness has you in its grasp.

So, what do we do about it? How do we battle something from within?

The most common strategy has been to look outside of ourselves: increase your time socializing and creating connections with other people.

Many whom you seek advice from; friends, therapists, parents, and mentors will point you in this direction.

“You need to get out more!” is the advice of the common man’s sage.

This is good advice but is only part of the story, as we’ll soon see.

Modernity, in all its glory, has made it harder than ever to sincerely connect with one another.

We need to feel connected with other people, it’s part of being a human animal—a principle deeper than conventional norms.

A great deal has disrupted our ability to attend to what’s in front of us and has instead built an economy based on immediate gratification.

Our framing of relationships themselves has been altered by this new economy.

Instead of maintaining presence with people in front of us, we, at the drop of a hat, turn ourselves towards something more interesting.

That seems to be by design, as many advertisers, creators, and businesses recognize that, in the 21st Century, attention is worth more than oil.

To capture that attention, devices, apps, and all other media is working overtime to squeeze every ounce of focus it can out of you, which means they have to be entertaining.

This isn’t a bad thing by its nature; after all, if things weren’t interesting we’d never learn, grow, or connect, which are all of the things we’re trying to do.

The trouble is that spending time with people does not equal time spent in constant entertainment.

Yet, that’s an oft-cited reason for both the beginning and dissolution of relationships, especially among younger people:

“They just weren’t fun anymore", or, "They're fun to be around".

Not to dismiss the necessity of fun and play in relationships; they're absolutely crucial to lasting bonds, but much of the advice and information around relationships has been reduced to the fleeting sensation of being entertained.

Our minds have been trained for entertainment, and digital media has been a (the) most devious culprit.

We demand that everything entertain us or else we trot along to something that will; like a spoiled toddler, we throw away anything that’s failed to satisfy our immediate desire.

Many will agree that social media has nerfed our minds and social abilities.

But social media isn’t entirely to blame.

Only the Lonely

While 1/3 of Americans report feeling lonely, young men report the highest numbers.

Over 2/3 of Men under 30 report feelings of loneliness.

Loneliness is a social maladaptation—a sign that the proper order was not maintained.

An order cannot be maintained if it's not first learned.

Culture is perhaps one of the most significant educators we have, as it directs nearly all formal activity (schooling, work, means of communication, etc.)

American culture emphasizes individualism.

Not just individualism (it's fundamentally a good thing to be an individual) but a rugged and isolated individualism that frames any reliance on others as a weakness.

A product of Western thought itself, individualism is something essential to developing our own will—the human faculty of action—yet can easily slide into despair if we’re untrained in how to be an individual.

Carl Jung regularly emphasized the need to become an individual and discussed how important it is for young men to educate themselves on how to do so:

“It is highly important for a young person who is still unadapted and has as yet achieved nothing, to shape the conscious ego as effectively as possible that is, to educate the will. Unless he is positively a genius he even may not believe in anything active within himself that is not identical with his will. He must feel himself a man of will, and he may safely depreciate everything else within himself or suppose it subject to his will-for without this illusion he can scarcely bring about a social adaptation.”

Failure to learn of one’s capacity to will—recognizing the active force within oneself—reduces the possibility of individuation and invites social maladaptation.

Individuation, as Jung calls it, is the process of developing an independent sense of Self; a development that demands the deepest wisdom of oneself and mastery over one’s thoughts.

How might someone fail to “shape the conscious ego”?

We might answer this question with another:

Can you accomplish much when you’re distracted all of the time?

Unlikely.

Looking back at Jung’s statement addressed to young people, it may be helpful to also consider what social adaptations are taking place during this particular stage to find, hopefully, something like the order we should be aiming at.

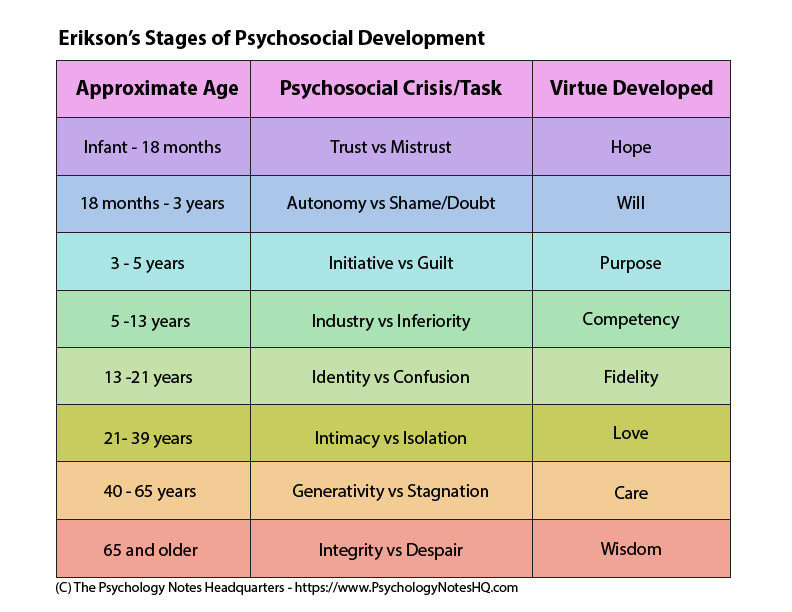

Erik Erikson, another well-known psychologist, provides us that answer.

He identified that humans go through 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development:

Many of the stages take place before adulthood, but one key stage of development begins right at the turn into adulthood and is key to our understanding of the problem of loneliness, especially in younger adults.

The specific stage that Erikson noticed individuals undergo in early adulthood was developing a sense of belonging in their relationships and rightly named it:

Intimacy vs Isolation.

Erikson did not see intimacy as something simply sexual, but rather as having integrity that breeds genuineness.

He deduced that young adults (roughly 20-35-year-olds) needed to form relationships and walk through their complexities in order to develop a sense of meaning, purpose, and connection.

Necessary to the development of intimacy with oneself and others is first a stable sense of identity:

"It is only after a reasonable sense of identity has been established that real intimacy with others can be possible. The youth who is not sure of his or her identity shies away from interpersonal intimacy, and can become, as an adult, isolated or lacking in spontaneity, warmth or the real exchange of fellowship in relationship to others; but the surer the person becomes of their self, the more intimacy is sought in the form of friendship, leadership, love and inspiration. The counterpart to intimacy is distantiation, which is the readiness to repudiate those forces and people whose essence seems dangerous to one’s own."

(Identity and the Life Cycle, 1959)

Erikson believed that each stage was built upon the other and that if an individual had failed to reach a stage's proper end, they would be stuck with the issues of the previous stage until a resolution was reached.

The person would struggle with the accompanying virtue of that stage so long as it remained unresolved.

Resolutions can occur, thankfully, beyond the age range that the individual develops that virtue, so long as a conscious effort is made in that direction.

In other words, so long as they have the capacity to will, as we learned from Jung.

The natural and logical alternative to the failed consolidation of identity is isolation.

Isolation not only in the sense of being physically isolated but also in the sense of being isolated from your sense of Self.

The person who failed to develop an identity failed to gain the virtue Erikson laid out as “Fidelity”; the root of which is “faith”.

Faith in what?

Faith that there is something more to being than that which is floating around in your mind, and also faith that it’d be good for you to engage with those unknown factors.

The Self develops in concert with our social connections.

Seeing what Erikson and Jung so clearly lay out, the answer to the loneliness epidemic is to learn, understand, and ultimately choose friendship.

First and foremost with ourselves and then with others.

Adulthood is the first time in an individual’s life where friendships, or at least the interactions that might lead to friendships, are no longer facilitated—they now bear the responsibility of choosing for themselves whether they interact with others.

This is where we understand the need to “educate the will”.

To get this right, we must understand that education is for the purpose of determining value.

Through education, we learn what to value.

A good education teaches value in proportion to virtue; that which leads to the excellence of the soul and the flourishing of mankind.

In the U.S. today, basic literacy remains high (around 99%), but functional literacy issues persist, with about 21% of adults having low functional literacy.

Paired with declines in major subject groups, reading and mathematics, this is a difficult situation we’re in.

The ability to use reading and writing is a vital piece to understanding the broader purpose and nuances of communication.

Not only that, the desire to read and write for its own sake has waned.

Reading is a way to acquire knowledge, while writing is how we consolidate it; these two things are pivotal in both self-discovery and learning more about what it means to be a person, which is key in consolidating an identity.

Without engaging in these powerful activities, we’re charting a course toward ruin.

A deficit in friendship walks hand in hand with a deficit in education.

Developing intimacy in our relationships is a two-part process.

Before we can expect to have an intimate connection with others, we must have a sense of intimacy within ourselves, which is produced only when we know a bit about who we are and have some semblance of an identity.

Our remedy for loneliness is then two-part: contemplation and community.

Contemplation is the activity that brings us into connection with ourselves, allows us to develop and refine our identity.

A community is that which we interact with and learn from, grow with, believe in, and acts as an additional source of personal reflection.

As we should keep all things in their proper order, let’s begin with contemplation.

Life Well Contemplated

For the lonely person, contemplation may seem like a blatantly paradoxical suggestion.

This is especially true when we consider that in order to effectively contemplate, we must be alone; contemplation is an exercise of solitude.

How could being alone be good for a lonely person?

As we discussed, the world we interact with daily is infected with distraction and noise.

Can you think clearly when you're distracted?

Do you understand the fullness of your actions when you constantly stand on the back foot?

Contemplation should be thought of as simply bringing awareness to what we value.

To discover your real values, you need to remove yourself as much as possible from stimuli that might otherwise alter your judgment—that might tip the balance due to a facade forged by the expectations of others.

This is why many of the greatest men in history spent extended periods of time in isolation; it wasn’t just to get away from people, it was so they might develop their consciences ego rather than being led by the spirit of their own impulses and the judgement of others.

Moses, DaVinci, Milton, Jesus Christ, Napoleon, Nietzsche…. you get the point.

Time spent with oneself is time spent learning of oneself and inevitably becoming a companion of your own.

Feeling lonely can be a result of spending too much time with others or otherwise occupied and not engaging with ourselves.

We form a persona in the presence of others, projecting what we think they want to see of us, setting aside our Self, that most dear personality that we only uncover when we’re utterly alone and free of external expectations.

Understanding what I (self) value is of the highest importance.

What we value necessarily determines our actions.

“The ultimate value of life depends upon awareness and the power of contemplation rather than upon mere survival.”

~Aristotle

How many people would say they’re living a life beyond “mere survival”?

To contemplate is to have that space to breathe and enter into self-questioning, where you ask yourself:

“Where have I been? Where am I going? Who am I?”

These three questions are the foundation for self-awareness. Without pause, without reflection, anything we learn simply gets tacked into our minds but not consolidated, integrated, and transformed.

Like paperwork that’s never been filed or shredded, it piles up over time into a huge cluttered, dreadful mess.

If we’re to educate ourselves—our will—this process cannot be neglected.

It’s through the consolidation of knowledge (aka writing) that we have a proper footing to begin to transform our knowledge.

The transformation of knowledge is the integration of what we know into the Self, which is where wisdom begins.

Through wisdom, we gain an awareness of ourselves, not just an awareness of “I” but also of “We”, of Mankind itself.

You’re a microcosm of humanity, what is in you (and absent) can show you what stands to be within all others.

It’s vital that you know this.

When we exercise our power of contemplation, not only are we entering into this essential state of reflection, we are exercising our will by the very process.

To contemplate is to challenge our natural focus on “mere survival” and the usual scurrying about, and instead bring our attention to things both beyond us and behind us, an act that cannot be done in a state of fight-or-flight.

Contemplation reminds us that we have a certain power over our world: “I happen upon the world”, rather than, “The world happens unto me”.

It’s an exercise that balances our locus of control and reminds us that we are the masters of our destiny and commanders of ourselves; something which could not be said prior to this act.

“Not all of us are called to be hermits, but all of us need enough silence and solitude in our lives to enable the deeper voice of our own self to be heard at least occasionally.”

~ Thomas Merton

This silence is sorely lacking in our modern world.

Instead of taking time to enter into contemplation, we sit and scroll our devices and binge on more and more information.

Young adults, particularly those who are 18-24 years old, tend to spend 9-10 hours daily on digital media, which encompasses browsing the web, using social media, streaming video, playing online games, and engaging in other digital activities.

Leisure, which facilitates contemplation, has become monopolized by an industry of distraction.

The person who has no other reason to avoid cheap hits of dopamine, who has not been educated on the value of refraining from constant and immediate pleasure, will rarely enter into this state. At least not of their own accord.

What typically happens to this untrained person is the torment of thoughts as they lay down for a night’s rest and they complain of insomnia and are unaware that the cure is structured time to think.

Instead of taking time to know themselves, they come to know no one… a fearful realization.

Take 15 minutes each day to sit with your own thoughts, begin with the ones I mentioned earlier and see where it leads you.

You can do this on a walk, which primes our minds for action and gets us in touch with nature—another activity that we’ve cast aside.

If you’d like, feel free to share your impressions by either commenting/replying to this post or reaching out to me in some other way, I’d love to hear from you!

United We Stand

Now that we’ve looked inward, it’s time to look outward.

Even if you feel comfortable being alone, or even prefer it, you still need to interact with others.

It’s essential to humanness.

As Aristotle said in his great work, Politics:

“He who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god.”

We’re meant for connection.

Our sanity is hidden in our communication with other people—they keep us in rhythm.

Discoveries in human neurobiology have shown that we have specific neurons dedicated strictly to mirroring other’s behaviors.

That’s why when I yawn, you are likely to follow suit.

What’s really neat about these neurons is that you don’t even have to see me in order to yawn, they will often fire at a mere word that you read. (I’ve yawned three four times while writing this, how many times did you yawn?)

This little trick of our minds is no accident.

The mirror neurons point to a broader point in our fundamental construction—synchronicity.

The need for attunement of one person to another is hardwired in our brains, so there's no use in trying to escape.

We need community.

Loneliness is not only a social maladaptation, it’s a result of not engaging properly in the interactions your brain desperately needs for proper growth and functioning.

According to the National Institute on Aging, prolonged periods of loneliness can shave up to 15 years off of a person's expected life span.

This isn’t a “well I’m an exception” kind of issue that we typically attribute to personality; it’s a necessary function of being human.

Friendship comes at a cost, though, so we shouldn’t ignore that piece.

Frequently, that cost is your own ego.

To enter into a friendship you have to say something like, “There’s some parts of me that aren’t as refined as they could be, and I think having someone along side me pointing out some of those weaknesses might be a good thing. And surely they have a similar issue, so I’ll promise them that I’ll do the same. That way the world doesn’t take us both out anytime our flaws show up.”

There’s a desire to improve that is enabled only by humility; if we are to learn we must remain humble.

While accurate, it’s still not the full picture.

Maybe, this is it:

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

John 15:13 (KJV)

Not only must there be humility, there is also the necessity for self-sacrifice when we are creating social connections.

Self-sacrificial love is the bedrock of all relationships bound for greatness.

While this is a lofty ideal, we can break this down into something more actionable.

If you’re struggling with loneliness, here are 5 things you can do to improve your sense of connection, belonging, and love for others:

Acts of Service: Engage in acts of service without expecting anything in return can foster deeper connections. This could involve helping neighbors with chores, volunteering at local shelters, or assisting community members in need. Such actions not only help others but also demonstrate that one's time and effort are valued, reducing feelings of isolation on both sides.

Open-Hearted Listening: Often, loneliness stems from feeling unheard or misunderstood. Practicing active, empathetic listening where you truly try to understand and feel what the other person is experiencing, without rushing to offer solutions or advice, can bring you into rhythm with someone else. This requires a sacrifice of one's own immediate needs for attention or to fix problems, focusing instead on the emotional support of others.

Sharing Vulnerabilities: By sharing personal stories, struggles, or vulnerabilities, one not only humanizes themselves but also invites others to do the same. This reciprocal vulnerability can break down barriers, showing that everyone has challenges, which can lead to mutual support and reduce the stigma of loneliness. It's about sacrificing the appearance of having it all together for the sake of genuine connection.

Community Building Projects: Initiating or participating in community projects where collective effort is needed (like community gardens, neighborhood watch programs, or local festivals) can build a sense of belonging. These projects require time, effort, and sometimes personal resources, embodying self-sacrificial love. They provide regular interaction and a shared purpose, which are antidotes to loneliness.

Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Holding onto grudges or past hurts can isolate individuals from community and personal relationships. Practicing forgiveness, even when it's not sought, demonstrates a form of self-sacrificial love where one chooses peace and reconciliation over resentment. This act can heal relationships, reduce personal stress, and mend community ties, directly combating loneliness by restoring connections that might have been severed. When we fail to do so, there are consequences.

Each of these actions requires stepping outside one's immediate self-interest, which is the essence of friendship.

By prioritizing the needs and emotional wellness of others, you not only contribute to cultivating a healthier, more connected community but may also find that your own feelings of loneliness diminish as you become integral parts of a supportive network.

“Love isn't something natural. Rather it requires discipline, concentration, patience, faith, and the overcoming of narcissism. It isn't a feeling, it is a practice.”

~ Erich Fromm

I’d love to talk more about the role narcissism plays in loneliness, but I’ll save that for another time.

Changing Your Pace

The significant number of young men reporting loneliness presents us with a daunting task:

How can we educate young men to form the bonds with themselves and others, pulling them away from potentially life-ending despair and isolation?

The full answer appears to lay within a response to Aristotle we discussed earlier, a response from the notorious Friedrich Nietzsche:

“To live alone one must be a beast or a god, says Aristotle. Leaving out the third case: one must be both — a philosopher”

I would say this is exactly my point and what I’ve attempted to lay out.

Don’t be alarmed, you needn’t go back to university or anything like that.

What you need is exactly as I’ve laid out — the intersection between the actions of the beast (community) and those of the divine (contemplation).

Part of discovering who we are and becoming who we could be is reaching for the ever-evolving needs of the Self.

A good life is a balanced life; one where we account for all of our individual needs, not ignore the essentials because it's not immediately pleasing.

Some of us need more time in contemplation to feel whole, while others require only a little.

You might be coming from a point where you think you know what you need, and that’s great.

What I'll say about the assumption, "I know who I am", is that it's important to distinguish between who you say you are and who you really are.

It's most often the case that the two are not in agreement.

When we find that we feel conflicted and dissatisfied—for the sake of this let’s say it’s loneliness—take a moment to draw back and lose the assumptions you’ve carried with you thus far, including the one I just mentioned.

Set them down and ask yourself those baseline contemplative questions, “Where have I been? Where am I going? Who am I?”

See what you come up with and whether you need to spend more time with yourself or others based upon your answer.

After some time passes—rinse and repeat.

This brief contemplation allows you the space to shift your focus from the automatic thoughts that compress and tangle in your mind throughout the day, to a clearer and more grounded mindset from which we can choose our actions.

This is, essentially, philosophy.

The “love” (philo) of “wisdom” (sophia).

“Philo” —> “philia”, meaning loving, is a specific kind of love the Greeks identified as “brotherly” or a love that’s the kind which exists between friends who want the best for another.

It’s a bit different than the “self-sacrificial” love we discussed earlier, which is agape.

Agape is simply the perfection of love itself, of which there’s no greater demonstration than to lay down your life, according to Christ.

So, to be more specific, philosophy is the process of making friends with wisdom.

Wisdom is knowing that you need to befriend your Self and others in order to accomplish a sense of belongingness.

Use the 5 ways I listed above to engage others in a meaningful display of affection and connection.

Each of these ways is a means to end the pattern of loneliness and grow firmly rooted connections with yourself and others.

For those still worried that they’re unable to meet the demands of these activities and overcome their loneliness, hang on just a little longer.

William James, the father of American Psychology and founder of the philosophy of Pragmatism, believed that we have a vital choice in how we feel and what we do:

“The greatest discovery of my generation is that a human being can alter his life by altering his attitude.”

This might sound a bit like, “fake it ‘til you make it”, and it is.

Ruminating on the same things day in and day out never really solves anything.

Sure, you’re “thinking about it” but it’s more like getting humiliated by your own mind and nothing that gets you closer to your goals.

“The purpose of knowledge is action, not knowledge.”

~Aristotle

It’s a harsh truth, but no amount of preparation will prepare you for what will actually happen or the sensation of being in a particular moment.

Your life is made up of what you do.

Sure, we can watch other people do things, or think through different scenarios which may give us added confidence to act, but we still need to act.

Use the motivation and set forth immediately.

Loneliness is often the result of inaction.

The solution?

Act.

How should you act?

In some manner toward improving your relationships with Self and others.

Thank you so much for reading!

Problems like these are why I created Reaching for More in the first place, so if you liked this article, please let me know by liking this post and sharing it so more people can learn, grow, and transform their lives!

See you next time.

xDevan